Masonry and Modernity

By Andy Smith - Columbia, South Carolina, USA - Advent/Christmas 2010

The stone which the builders rejected has become the cornerstone.

Psalm 118:22

Dad was a stone mason -- and a rather talented one. He had an incredibly keen eye, perceiving the potential for ordered beauty latent within an otherwise chaotic assemblage of Tennessee riverrock, Carolina granite, Virginia slate. His preference, beyond a doubt, was to work with the irregular stones of rubble masonry rather than the tidy perfection of ashlar. And, there was certainly to be no suggestion of brick.

But, Dad was also an alcoholic. The demons which haunted his soul in this regard were as unrelentingly piercing as the most obstinately jagged stones from which he created stately order. It was almost as though this outer order were overcompensation for an inner order he could never, of his own volition, attain: the same sort of inner order at which we all, excepting the saints perhaps (albeit through grace), fail to arrive -- while on this plane of existence, at any rate.

But, Dad was also an alcoholic. The demons which haunted his soul in this regard were as unrelentingly piercing as the most obstinately jagged stones from which he created stately order. It was almost as though this outer order were overcompensation for an inner order he could never, of his own volition, attain: the same sort of inner order at which we all, excepting the saints perhaps (albeit through grace), fail to arrive -- while on this plane of existence, at any rate.

The clue to connecting Dad’s labor and this particular neurosis very likely lies, I’ve come to suspect, in his penchant for the nostalgic. His mind was often occupied with a pristine past in which even he had never lived -- a perfection that even he couldn’t articulate. He loved the simple, redemptive subtleties of the Andy Griffith Show, harboring a specific appreciation of its unsullied, if sterile, pre-60’s humor. He recognized that there was no need, at least while in the presence of his own child, to resort to cynicism, scandal, or perversion to evoke a laugh or to speak of life’s oddities. Also, he loved the show’s frequent vindication of the rube. (So great was his love, that he dubbed his beloved boston terrier Barney; a feisty pug mix, Thelma Lou; a nomadic tomcat, Otis; and the goat, Aunt Bee. Everyone but he insisted that I was named after the apostle.) Then, of course, there was his love for finding and collecting Native American artifacts, never ceasing to experience intrigue in their elegance or to speculate about the techniques and motivations of the associated artisan. He relished the journey into the lives of forebears—and, he was increasingly captivated the more historically distant the circumstances.

Now, I don’t mean to suggest that Dad’s outlook was a paragon of the traditional worldview. His was not a purely pontifical perception (in the broadest sense of pontifical, i.e., as the description of the inherent, if latent, verticality imbedded in the human condition). It can’t be ignored, after all, that he took as his craftsmanship’s mantra the title of a power ballad by Queen, that most promethean of 1980’s hair bands. He and his comrades would most certainly, if the slogan on his business card were any indication, rock you.

Nevertheless, while imbibing the despair-inducing trends of modern culture, his heart undoubtedly longed for something more substantial, something primordial, something vertical. So the question arises: Can I then, in my heart of hearts, really blame him for his turn toward the therapeutic comforts of drink?

My mentioning Dad’s alcoholism here, though, is intended neither as an impetus to slip into some sort of determinism, materialist or otherwise (excusing moral culpability and ignoring the God-given ability to address limitations through restraint, self-reflection, and confession, i.e., the appropriate exercising of one’s free will) nor, for that matter, as a denigration of his character in an attempt to explain, among other things, the particular neuroses and flaws of his progeny (though they may be many). Rather, the purpose here is to prompt contemplation about modernity and its unhealthy treatment of traditional categories -- in this case, craftsmanship and human vocation.

My mentioning Dad’s alcoholism here, though, is intended neither as an impetus to slip into some sort of determinism, materialist or otherwise (excusing moral culpability and ignoring the God-given ability to address limitations through restraint, self-reflection, and confession, i.e., the appropriate exercising of one’s free will) nor, for that matter, as a denigration of his character in an attempt to explain, among other things, the particular neuroses and flaws of his progeny (though they may be many). Rather, the purpose here is to prompt contemplation about modernity and its unhealthy treatment of traditional categories -- in this case, craftsmanship and human vocation.

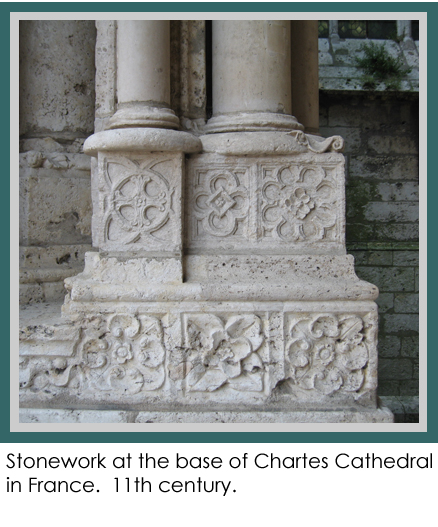

If living in another era, Dad likely would have had at least the opportunity to orient his life toward the Good within the limiting (i.e. sanctifying) parameters of his craft -- situating his labor within a framework that saw stone work on this plane of existence as the foundation and mirror of the creation of the heavenly temple, the stone mason participating, as it were, in the divine archetype. Such profound meaning would likely have been incorporated into the brotherhood of the initiatory guild, evoking within the craftsman the fortitude to proceed along the way of acknowledged, though hidden, transcendence. It’s not for nothing that medieval stone-workers, for example, could devote their entire lives to a cathedral project they knew they would never see completed.

As it was, however -- in the latest, most deranged of days around the turn of the 21st century -- Dad was relegated to that loose collective assigned the maligned moniker “manual laborers.” In the eyes of moderns, he and his type had simply become blue collar (albeit in a less noticeably overt manner than those manning the conveyor belts of spirit-deprived machination). His vocation was suddenly expendable -- replaced by the job of untrained, unskilled handymen charged with the unthinking task of sticking thin, synthetic stone to the outside of an existing cinder-block structure, rather than the robust responsibility of building the structure with natural stone such that the stone was an integral component of the construction, the presence of cinder-block notwithstanding. This move is nothing short of a rejection -- on par, dare I say, with the refusal to contend, for example, with Dad’s intuition of a pristine past, which is to say, with Man’s clouded recollection of an Edenic state.

The Psalmist reminds us, though: “the stone the builders rejected has become the cornerstone.”

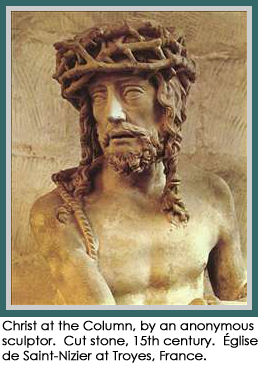

The Great Tradition understands this cornerstone to be none other than Christ. He is the logos who takes on our lot, entering the world to sanctify, such that the inner life of fallen man -- characterized as it is by division and chaotic aimlessness -- might be solidified around the stabilizing presence of a cornerstone and ordered toward a specific, constructive, transcendent end.

While the cornerstone has repeatedly been rejected, modern humans have, in a uniquely potent way, cast aside this ordering principle -- this logos -- and, with it, the end to which He orders. Just as contemporary “stone masons” have forsaken the quarried beauties of the Appalachian hills for the synthetic banalities of the stone factory -- relenting to the suburban drive for cookie cutter efficiency and faux-stability -- all while forgetting what it is that they’re supposed to be constructing (i.e., humane dwellings), modernity has rejected the given cornerstone, for any number of the easily-eroding sandstones of its own making.

The machine now creates and shapes stones -- the latter a task once charged solely to that being who is none other than the imago dei. And, subtly -- imperceptibly almost -- our understanding of the human state, no longer perceived within the context of the redemptive work of the logos, is lowered: the craftsman with an eye to the transcendent becoming the Sisyphean manual laborer, pontifical man shuttered beneath the promethean. And many who would become noble succumb to the neuroses that render them helpless -- or to the Prozac that helps them cope.

Of course, the helplessness is not without hope: the tradition says that the logos will return, and His kingdom will have no end. The rejected will indeed once again become the corner. But, the cost -- as this Lenten season reminds us -- is great.

Dad was diagnosed with cancer a few years ago. He lived three additional months after the diagnosis, and died just after his 51st birthday. Never have I witnessed such a level of emaciation; never, such a profound journey along the way of the cross. He taught me more in those three months than he did in my previous 24 years -- all while maintaining the sly sense of humor of the world-weary artisan. Despite this humor -- perhaps even in concert with it -- a certain ordering sobriety prevailed in the face of death: a glimpse, perhaps, of the ultimate transcendent meaning of his life and vocation. At the end, his frail face, as the hospice nurses were quick to point out, marked his exit from this world with a slight smile.

The rejected stone, in the final analysis it seems, had become the cornerstone.