Keeping Fast and Festival

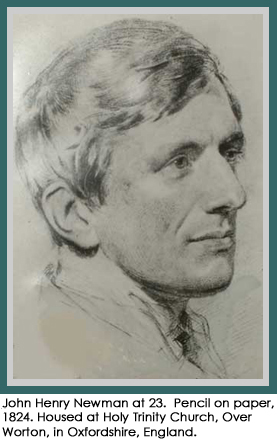

By Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman (1801-1890)

"A time to weep, and a time to laugh: a time to mourn, and a time to dance." Eccles. iii. 4.

At Christmas we joy with the natural, unmixed joy of children, but at Easter our joy is highly wrought and refined in its character. It is not the spontaneous and inartificial outbreak which the news of Redemption might occasion, but it is thoughtful; it has a long history before it, and has run through a long course of feelings before it becomes what it is. It is a last feeling and not a first. St. Paul describes its nature and its formation, when he says, "Tribulation worketh patience, and patience experience, and experience hope; and hope maketh not ashamed, because the love of God is shed abroad in our hearts by the Holy Ghost which is given unto us." [Rom. v. 3-5.] And the prophet Isaiah, when he says, "They joy before Thee according to the joy in harvest, and as men rejoice when they divide the spoil." [Isa. ix. 3.] Or as it was fulfilled in the case of our Lord Himself, who, as being the Captain of our salvation, was made perfect through sufferings. Accordingly, Christmas Day is ushered in with a time of awful expectation only, but Easter Day with the long fast of Lent, and the rigours of the Holy Week just past: and it springs out and (as it were) is born of Good Friday.

At Christmas we joy with the natural, unmixed joy of children, but at Easter our joy is highly wrought and refined in its character. It is not the spontaneous and inartificial outbreak which the news of Redemption might occasion, but it is thoughtful; it has a long history before it, and has run through a long course of feelings before it becomes what it is. It is a last feeling and not a first. St. Paul describes its nature and its formation, when he says, "Tribulation worketh patience, and patience experience, and experience hope; and hope maketh not ashamed, because the love of God is shed abroad in our hearts by the Holy Ghost which is given unto us." [Rom. v. 3-5.] And the prophet Isaiah, when he says, "They joy before Thee according to the joy in harvest, and as men rejoice when they divide the spoil." [Isa. ix. 3.] Or as it was fulfilled in the case of our Lord Himself, who, as being the Captain of our salvation, was made perfect through sufferings. Accordingly, Christmas Day is ushered in with a time of awful expectation only, but Easter Day with the long fast of Lent, and the rigours of the Holy Week just past: and it springs out and (as it were) is born of Good Friday.

On such a day, then, from the very intensity of joy which Christians ought to feel, and the trial which they have gone through, they will often be disposed to say little. Rather, like sick people convalescent, when the crisis is past, the illness over, but strength not yet come, they will go forth to the light of day and the freshness of the air, and silently sit down with great delight under the shadow of that Tree, whose fruit is sweet to their taste. They are disposed rather to muse and be at peace, than to use many words; for their joy has been so much the child of sorrow, is of so transmuted and complex a nature, so bound up with painful memories and sad associations, that though it is a joy only the greater from the contrast, it is not, cannot be, as if it had never been sorrow.

And in this too the feeling at Easter is not unlike the revulsion of mind on a recovery from sickness, that in sickness also there is much happens to us that is strange, much that we must feebly comprehend and vaguely follow after. For in sickness the mind wanders from things that are seen into the unknown world, it turns back into itself, and is in company with mysteries; it is brought into contact with objects which it cannot describe, which it cannot ascertain. It sees the skirts of powers and providences beyond this world, and is at {336} least more alive, if not more exposed to the invisible influences, bad and good, which are its portion in this state of trial. And afterwards it has recollections which are painful, recollections of distress, of which it cannot recall the reasons, of pursuits without an object, and gleams of relief without continuance. And what is all this but a parallel feeling to that, with which the Christian has gone through the contemplations put before his faith in the week just passed, which is to him as a fearful harrowing dream, of which the spell is now broken? The subjects, indeed, which have been brought before him are no dream, but a reality, -- his Saviour's sufferings, his own misery and sin. But, alas! to him at best they are but a dream, because, from lack of faith and of spiritual discernment, he understands them so imperfectly. They have been to him a dream, because only at moments his heart has caught a vivid glimpse of what was continually before his reason, -- because the impression it made upon him was irregular, shifting, and transitory,—because even when he contemplated steadily his Saviour's sufferings, he did not, could not understand the deep reasons of them, or the meaning of His Saviour's words, -- because what most forcibly affected him came through his irrational nature, was not of the mind but of the flesh, not of the scenes of sorrow which the Lessons and Gospels record, but of his own discomfort of body, which he has been bound, as far as health allows, to make sympathize with the history of those sufferings which are his salvation. And thus I say his disquiet during the week has been like that of a bad dream, restless and dreary; he has felt he ought to be very sorry, and could not say why, -- could not master his grief, could not realize his fears, but was as children are, who wonder, weep, and are silent, when they see their parents in sorrow, from a feeling that there is something wrong, though they cannot say what.

And therefore now, though it is over, he cannot so shake off at once what has been, as to enter fully into what is. Christ indeed, though He suffered and died, yet rose again vigorously on the third day, having loosed the pains of death; but we cannot accomplish in our contemplation of Him, what He accomplished really; for He was the Holy One, and we are sinners. We have the languor and oppression of our old selves upon us, though we be new; and therefore we must beg Him who is the Prince of Life, the Life itself, to carry us forth into His new world, for we cannot walk thither, and seat us down whence, like Moses, we may see the land, and meditate upon its beauty!

And yet, though the long season of sorrow which ushers in this Blessed Day, in some sense sobers and quells the keenness of our enjoyment, yet without such preparatory season, let us be sure we shall not rejoice at all. None rejoice in Easter-tide less than those who have not grieved in Lent. This is what is seen in the world at large. To them, one season is the same as another, and they take no account of any. Feast-day and fast-day, holy tide and other tide, are one and the same to them. Hence they do not realize the next world at all. To them the Gospels are but like another history; a course of events which took place eighteen hundred years since. They do not make our Saviour's life and death present to them: they do not transport themselves back to the time of His sojourn on earth. They do not act over again, and celebrate His history, in their own observance; and the consequence is, that they feel no interest in it. They have neither faith nor love towards it; it has no hold on them. They do not form their estimate of things upon it; they do not hold it as a sort of practical principle in their heart. This is the case not only with the world at large, but too often with men who have the Name of Christ in their mouths. They think they believe in Him, yet when trial comes, or in the daily conduct of life, they are unable to act upon the principles which they profess: and why? because they have thought to dispense with the religious Ordinances, the course of Service, and the round of Sacred Seasons of the Church, and have considered it a simpler and more spiritual religion, not to act religiously except when called to it by extraordinary trial or temptation; because they have thought that, since it is the Christian's duty to rejoice evermore, they would rejoice better if they never sorrowed and never travailed with righteousness. On the contrary, let us be sure that, as previous humiliation sobers our joy, it alone secures it to us. Our Saviour says, "Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall he comforted;" and what is true hereafter, is true here. Unless we have mourned, in the weeks that are gone, we shall not rejoice in the season now commencing. It is often said, and truly, that providential affliction brings a man nearer to God. What is the observance of Holy Seasons but such a means of grace?

This too must be said concerning the connexion of Fasts and Feasts in our religious service, viz., that that sobriety in feasting which previous fasting causes, is itself much to be prized, and especially worth securing. For in this does Christian mirth differ from worldly, that it is subdued; and how shall it be subdued except that the past keeps its hold upon us, and while it warns and sobers us, actually indisposes and tames our flesh against indulgence? In the world feasting comes first and fasting afterwards; men first glut themselves, and then loathe their excesses; they take their fill of good, and then suffer; they are rich that they may be poor; they laugh that they may weep; they rise that they may fall. But in the Church of God it is reversed; the poor shall be rich, the lowly shall be exalted, those that sow in tears shall reap in joy, those that mourn shall be comforted, those that suffer with Christ shall reign with Him; even as Christ (in our Church's words) "went not up to joy, but first He suffered pain. He entered not into His glory before He was crucified. So truly our way to eternal joy is to suffer here with Christ, and our door to enter into eternal life is gladly to die with Christ, that we may rise again from death, and dwell with him in everlasting life." And what is true of the general course of our redemption is, I say, fulfilled also in the yearly and other commemorations of it. Our Festivals are preceded by humiliation, that we may keep them duly; not boisterously or fanatically, but in a refined, subdued, chastised spirit, which is the true rejoicing in the Lord.

In such a spirit let us endeavour to celebrate this most holy of all Festivals, this continued festal Season, which lasts for fifty days, whereas Lent is forty, as if to show that where sin abounded, there much more has grace abounded. Such indeed seems the tone of mind which took possession of the Apostles when certified of the Resurrection; and while they waited for, or when they had the sight of their risen Lord. If we consider, we shall find the accounts of that season in the Gospels, marked with much of pensiveness and tender and joyful melancholy; the sweet and pleasant frame of those who have gone through pain, and out of pain receive pleasure. Whether we read the account of St. Mary Magdalen weeping at the sepulchre, seeing Jesus and knowing Him not, recognizing His voice, attempting to embrace His feet, and then sinking into silent awe and delight, till she rose and hastened to tell the perplexed Apostles;—or turn to that solemn meeting, which was the third, when He stood on the shore and addressed His disciples, and Peter plunged into the water, and then with the rest was awed into silence and durst not speak, but only obeyed His command, and ate of the fish in silence, and so remained in the presence of One in whom they joyed, whom they loved, as He knew, more than all things, till He broke silence by asking Peter if he loved Him: -- or lastly, consider the time when He appeared unto a great number of disciples on the mountain in Galilee, and all worshipped Him, but some doubted: -- who does not see that their Festival was such as I have been describing it, a holy, tender, reverent, manly joy, not so manly as to be rude, not so tender as to be effeminate, but (as if) an Angel's mood, the mingled offering of all that is best and highest in man's and woman's nature brought together, -- St. Mary Magdalen and St. Peter blended into St. John? And here perhaps we learn a lesson from the deep silence which Scripture observes concerning the Blessed Virgin after the Resurrection; as if she, who was too pure and holy a flower to be more than seen here on earth, even during the season of her Son's humiliation, was altogether drawn by the Angels within the veil on His Resurrection, and had her joy in Paradise with Gabriel who had been the first to honour her, and with those elder Saints who arose after the Resurrection, appeared in the Holy City, and then vanished away.

May we partake in such calm and heavenly joy; and, while we pray for it, recollecting the while that we are still on earth, and our duties in this world, let us never forget that, while our love must be silent, our faith must be vigorous and lively. Let us never forget that in proportion as our love is "rooted and grounded" in the next world, our faith must branch forth like a fruitful tree into this. The calmer our hearts, the more active be our lives; the more tranquil we are, the more busy; the more resigned, the more zealous; the more unruffled, the more fervent. This is one of the many paradoxes in the world's judgment of him, which the Christian realizes in himself. Christ is risen; He is risen from the dead. We may well cry out, "Alleluia, the Lord Omnipotent reigneth." He has crushed all the power of the enemy under His feet. He has gone upon the lion and the adder. He has stopped the lion's mouth for us His people, and has bruised the serpent's head. There is nothing impossible to us now, if we do but enter into the fulness of our privileges, the wondrous power of our gifts. The thing cannot be named in heaven or earth within the limits of truth and obedience which we cannot do through Christ; the petition cannot be named which may not be accorded to us for His Name's sake. For, we who have risen with Him from the grave, stand in His might, and are allowed to use His weapons. His infinite influence with the Father is ours, -- not always to use, for perhaps in this or that effort we make, or petition we prefer, it would not be good for us; but so far ours, so fully ours, that when we ask and do things according to His will, we are really possessed of a power with God, and do prevail: -- so that little as we may know when and when not, we are continually possessed of heavenly weapons, we are continually touching the springs of the most wonderful providences in heaven and earth; and by the Name, and the Sign, and the Blood of the Son of God, we are able to make devils tremble and Saints rejoice. Such are the arms which faith uses, small in appearance, yet "not carnal, but mighty through God to the pulling down of strongholds;" [2 Cor. x. 4.] despised by the world, what seems a mere word, or a mere symbol, or mere bread and wine; but God has chosen the weak things of the world to confound the mighty, and foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and as all things spring from small beginnings, from seeds and elements invisible or insignificant, so when God would renew the race of man, and reverse the course of human life and earthly affairs, He chose cheap things for the rudiments of His work, and bade us believe that He could work through them, and He would do so. As then we Christians discern in Him, when He came on earth, not the carpenter's son, but the Eternal Word Incarnate, as we see beauty in Him in whom the world saw no form or comeliness, as we discern in that death an Atonement for sin in which the world saw nothing but a malefactor's sentence; so let us believe with full persuasion that all that He has bequeathed to us has power from Him. Let us accept His Ordinances, and His Creed, and His precepts; and let us stand upright with an undaunted faith, resolute, with faces like flint, to serve Him in and through them; to inflict them upon the world without misgiving, without wavering, without anxiety; being sure that He who saved us from hell through a Body of flesh which the world insulted, tortured, and triumphed over, much more can now apply the benefits of His passion through Ordinances which the world has lacerated and now mocks.

This then, my brethren, be our spirit on this day. God rested from His labours on the seventh day, yet He worketh evermore. Christ entered into His rest, yet He too ever works. We too, if it may be said, in adoring and lowly imitation of what is infinite, while we rest in Christ and rejoice in His shadow, let us too beware of sloth and cowardice, but serve Him with steadfast eyes yet active hands; that we may be truly His in our hearts, as we were made His by Baptism, -- as we are made His continually, by the recurring celebration of His purifying Fasts and holy Feasts.

Nota bene: The text of this sermon is taken from W.J. Copeland, ed., "Sermon XXIII," Selections Adapted to the Seasons of the Ecclesiastical Year from the Parochial and Plain Sermons of John Henry Newman, B.D. (London: Rivingtons, 1878), 189-195.