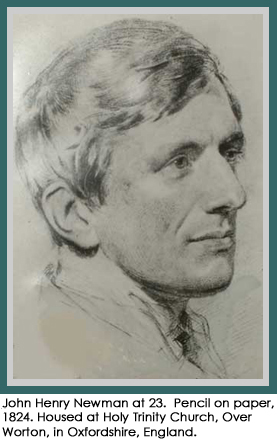

Newman the Controversialist (1905)

Henri Brémond (1865-1933) - Bordeaux and Paris, France

The following text is excerpted from Newman: Essai de biographie psychologique (Paris: Librairie Bloud et Cie., 1906) as translated by H.C. Corrance (London: Williams and Norgate, 1907). The text appears on pages 48-57 of Corrance's edition.

The study of Newman's sensibility would not be complete if I did not say at least some words about the fine fits of passion which enliven, sustain, and sometimes lead astray his controversial works. Legend, shaping the image of this great man according to the prompting of its own desires, has left in the shade this characteristic feature. It sees in Newman only the pacific and conciliatory defender of the Faith, respecting above all the liberty of souls, and who would look upon it as a crime to quench the smoking flax. After all, legend is right. If he never was, at any moment of his life, the dupe of what he thought the Liberal illusion, if the modern conception of tolerance never inspired in him anything but a holy horror, the true Newman is not a fanatic. Himself under suspicion during many years, he learnt at his own expense what bitter suffering precipitate anathemas can cause to men of goodwill. He followed with a great number of distressed believers the disastrous effects of religious polemics. He understood that the best way of leading men to a conquest of the whole truth was to disentangle, to respect, to encourage, to guide in short, that spirit of truth which the worst errors never choke in a sincere heart. It can be said, then, with one of the most eminent experts of the England of to-day, that Newman went against his true nature when he abandoned himself to the one-sided eagerness of controversy. "Many," wrote Hort, "of his sayings and doings I cannot but condemn most strongly. But they are not Newman." [1]

The study of Newman's sensibility would not be complete if I did not say at least some words about the fine fits of passion which enliven, sustain, and sometimes lead astray his controversial works. Legend, shaping the image of this great man according to the prompting of its own desires, has left in the shade this characteristic feature. It sees in Newman only the pacific and conciliatory defender of the Faith, respecting above all the liberty of souls, and who would look upon it as a crime to quench the smoking flax. After all, legend is right. If he never was, at any moment of his life, the dupe of what he thought the Liberal illusion, if the modern conception of tolerance never inspired in him anything but a holy horror, the true Newman is not a fanatic. Himself under suspicion during many years, he learnt at his own expense what bitter suffering precipitate anathemas can cause to men of goodwill. He followed with a great number of distressed believers the disastrous effects of religious polemics. He understood that the best way of leading men to a conquest of the whole truth was to disentangle, to respect, to encourage, to guide in short, that spirit of truth which the worst errors never choke in a sincere heart. It can be said, then, with one of the most eminent experts of the England of to-day, that Newman went against his true nature when he abandoned himself to the one-sided eagerness of controversy. "Many," wrote Hort, "of his sayings and doings I cannot but condemn most strongly. But they are not Newman." [1]

There are, then, several pages of Newman that the most devoted admiration would banish from his work. [2] The same writer remarks:

He seemed to revel in religious warfare, and as a combatant he was bitter and scornful beyond all measure. . . . But the temptation to use his remarkable controversial powers unscrupulously must have been too strong for him; and so towards opponents, or those whom he chose to consider such, it is sadly uncommon to find him showing gentleness, or forebearance, or even common fairness. It was so both at Oxford and in his early Roman Catholic days. Then came the collision with Kingsley -- a tragic and shameful business. Kingsley was much to blame for his recklessly exaggerated epigram, though it had but too sad a foundation of truth. Newman's reply, however, was sickening to read, from the cruelty and insolence with which he trampled on his assailant. Kingsley's rejoinder was bad enough, but not so horribly un-Christian. [3]

These lines are those of an Anglican, wounded in his inmost feelings by the pitiless sarcasms which Newman lavished upon Anglicanism. Nevertheless, an impartial critic will not hesitate to recognise that, on the whole, these remarks are just. Full of nerves and irritability, not entirely master of his first impulses, impatient of all contradiction, Newman, in the early vigour of his Tractarian works and in the new-born zeal of a convert, is too often unjust and without pity for his adversary. Evidently he takes a singular pleasure in the battle; terrible in the heat of his disdainful irony, still more terrible, perhaps, when, with timid hand, he seems to hesitate to deliver the blows. The lectures on "The Prophetical Office of the Church," directed equally against Rome and against extreme Protestantism, furnish us with a finished model of this second manner. I do not remember to have ever read anything more suavely treacherous, more specious, or, at bottom, more violent, against us.

To enable the reader to judge, I cull this specimen from the third lecture:

We must take and deal with things as they are, not as they pretend to be. If we are induced to believe the professions of Rome, and make advances towards her as if a sister or a mother Church, which in theory she is, we shall find too late that we are in the arms of a pitiless and unnatural relative, who will but triumph in the arts which have inveigled us within her reach. No; dismissing the dreams which the romance of early Church history and {84} the high doctrines of Catholicism will raise in the inexperienced mind, let us be sure that she is our enemy, and will do us a mischief when she can. In speaking and acting on this conviction, we need not depart from Christian charity towards her. We must deal with her as we would towards a friend who is not himself; in great affliction, with all affectionate tender thoughts, with tearful regret and a broken heart, but still with a steady eye and a firm hand. For in truth she is a Church beside herself; abounding in noble gifts and rightful titles, but unable to use them religiously; crafty, obstinate, wilful, malicious, cruel, unnatural, as madmen are. Or rather, she may be said to resemble a demoniac; possessed with principles, thoughts, and tendencies not her own; in outward form and in natural powers what God has made her, but ruled within by an inexorable spirit, who is sovereign in his management over her, and most subtle and most successful in the use of her gifts. Thus she is her real self only in name; and, till God vouchsafe to restore her, we must treat her as if she were that evil one which governs her. [4]

Long after, he reproached the author of the "Eirenicon" for using a catapult in offering Catholics the olive-branch of peace. Here, likewise, the "tearful regret" and the "broken heart" take away nothing from the force of the club-like blow. One would prefer less tears and more moderation in the attack. But the fact is that Newman is provoked to hear it whispered all round him that he is playing the game of the Roman Babylon, and, in spite of himself, he forces the note. Besides, we are only at the beginning. The rest of the discourse tramples light heartedly on the victim who had been knocked down already by this first blow. Notice with what subtle facility, mixing the true and the false, he steals (sit venia verbo} a conclusion which goes far beyond his plain premisses.

He mislikes the doctrine of the infallibility of the Church. After having shown, as his first point, that Rome, in claiming for herself infallibility, suppresses the idea even of mystery, he passes on to the moral consequences of this dogma:

One more remark shall be made, though, as it is often urged in controversy, a few words on the subject will suffice. Romanism, by its pretence of infallibility, lowers the standard and quality of Gospel obedience as well as impairs its mys terious and sacred character; and this in various ways. When religion is reduced in all its parts to a system, there is hazard of something earthly being made the chief object of our contemplation instead of our Maker. Now, Romanism classifies our duties and their rewards, the things to be lieve, the things to do, the modes of pleasing God, the penalties and the remedies of sin, with such exactness, that an individual knows (so to speak) just where he is upon his journey heavenward, how far he has got, how much he has to pass, and his duties become a matter of calculation. It provides us with a sort of graduated scale of devotion and obedience, and engrosses our thoughts with the details of a mere system, to a comparative forgetfulness of its professed Author. But it is evident that the purest religious services are those which are done, not by constraint, but voluntarily, as a free offering to Almighty God. There are certain duties which are indispensable in all Christians, but their limits are undefined, to try our faith and love. instance, what portion of our worldly substance we should de vote to charitable uses, or in what way we are to fast, or how we are to dress, or whether we should remain single, or what revenge we should take upon our sins, or what amusements are allowable, or how far we may go into society; these and similar questions are left open by Inspiration. Some of them are determined by the Church, and suitably, with a view to public decency and order, or by way of recommendation and sanction to her members. A command from authority is to a certain point a protection to our modesty, though beyond this it would act as a burden . . . . But in most matters of the kind, certainly when questions of degree are concerned, the best rule seems to be to leave individuals free, lest what otherwise would be a spontaneous service in the more zealous, should become a compulsory enactment upon all. This is the true Christian liberty, not the prerogative of obeying God, or not, as we please, but the opportunity of obeying Him more strictly without formal commandment. In this way, too, the delicacy and generous simplicity of our obedience is consulted, as well as our love put to trial. Christ loves an open-hearted service, done without our con templating or measuring what we do, from the fulness of affection and reverence, while the mind is fixed on its great Object without thought of itself. Now express commands lead us to reflect upon and estimate our advances towards perfection, whereas true faith will mainly contemplate its deficiencies, not its poor attainments, whatever they be. It does not like to realise to itself what it does; it throws off the thought of it; it is carried on and reaches forward towards perfection, not counting the steps it has ascended, but keeping the end steadily in its eye, knowing only that it is advancing, and glorying in each sacrifice or service which it is allowed to offer, as it occurs, not remembering it after wards. But in Romanism there would seem to be little room for this unconscious devotion. Each deed has its price, every quarter of the land of promise is laid down and de scribed. Roads are carefully marked out, and such as would attain to perfection are constrained to move in certain lines, as if there were a science of gaining Heaven. Thus the saints are cut off from the Christian multitude by certain fixed duties, not rising out of it by the continuous growth and flowing forth of services which, in their substance, pertain to all men. And Christian holiness, in consequence, loses its freshness, vigour, and comeliness, being frozen (as it were) into certain attitudes, which are not graceful except when unstudied.

Frequent qualifications, such as "almost," and "so to speak," show that the orator has, by flashes, a consciousness of his injustice. In 1837 he had already known this too long to express himself in this fashion without imperceptible remorse. But his own affirmations reassure him, and he concludes boldly that the dogma of infallibility no longer runs the risk of fostering, but does foster, "a formal or carnal view of Christian obedience." [5]

The lecture which follows is no less astonishing. There is always the same apparent moderation, which restrains its in vectives only that they may carry further. He wishes to show that we hold cheap the witness of the Fathers and that we should be very glad to throw antiquity overboard. Of course, I speak only of hardened controversialists, not of Romanists in general, among whom, I doubt not, are many whose names are written in Heaven, minds as high, as pure, as reverential as any of those old Fathers, whose writings are in question; loyally attached to them, jealous of their honour, in that same noble English spirit, as it may be called, which we have already seen exemplified in Bishop Bull. I am but speaking of the Papist as found on the stage of life, and amid the excitement of controversy, stripped of those better parts of his system, which are our inheritance as well as his; and so contemplating him, surely I may assert without breach of charity, that he would, under circumstances, destroy the Fathers writings, as he actually does disparage their authority. [6]

In the same spirit, a few pages higher, he denounces with blazing indignation the "crime," the "parricide" of Petau, guilty of having maintained that the antenicene Fathers had erred in respect to the doctrine of the Trinity. [7]

In those days of hesitation and of fever he did not show himself either more conciliatory or more fair towards his brother Anglicans. Of Thomas Arnold, of Maurice, he seems to have seen only the errors. I feel sure that in his famous controversy with Hampden he read the writings of his opponent very quickly, or else that he read them with the unconscious prepossession of rinding them in error. I am not defending Hampden s orthodoxy; I only say that Newman s trenchant

pamphlet betrays an evident prejudice. It belongs to party polemics, and we cannot flatter ourselves that we have the thought of the true Newman on this capital question.

This same impetuosity breaks out in a perhaps still more unfortunate manner in his admirable novel "Loss and Gain." People must be very prejudiced who are able to read this book without a feeling of painful surprise, and I am sorry for those admirers of Newman who are not grieved to see him so far forget himself. Often, in reading this book, one feels inclined to repeat with Lanoue, "It is our wars for religion which have made us forget what religion is." [8] As a Catholic he

certainly had the right to show the inconsistencies of Anglicanism, but I shall never be persuaded that he was obeying the Spirit of God when he allowed himself to ridicule the religion of his mother, of Keble, of Pusey, and of so many beautiful souls. "It is very painful," writes Hort of "Loss and Gain," "in the early part, from the sneers at the Prayer-book, &c." [9] I add that the series of caricatures which so uselessly retard the unravelling of the plot are not one whit more pleasing. That irony, always out of place, seems to me twice as displeasing from the pen of a convert. And what poor irony sometimes! Charles, on the eve of his reception, a prey to that anguish which Newman could describe so fully, is just about to choose some books in a shop. The door opens. He turns his head :

It was a young clergyman, with a very pretty girl on his arm, whom her dress pronounced to be a bride. Love was in their eyes, joy in their voice, and affluence in their gait and bearing. Charles had a faintish feeling come over him, somewhat such as might beset a man on hearing a call for pork chops when he was sea-sick. He retreated behind a pile of ledgers and other stationery, but they could not save him from the low thrilling tones which from time to time passed from one to the other. [10]

Did he really write this, and would he, who lived among the dead, have had the courage to read these lines to the charming phantoms of his young sister Mary and of the wife

of Pusey? [11]

There came a day when Newman, at length quite himself, repulsed with warm eloquence the irreconcilables of Catholic controversy.

What I felt deeply, and ever shall feel, while life lasts, is the violence and cruelty of journals and other publications, which, taking, as they professed to do, the Catholic side, employed themselves by their rash language (though, of course, they did not mean it so) in unsettling the weak in faith, throwing back inquirers, and shocking the Protestant mind. Nor do I speak of publications only; a feeling was too prevalent in many places that no one could be true to God and His Church who had any pity on troubled souls, or any scruple of "scandalising those little ones who believe in" Christ, and of "despising and destroying him for whom He died." [12]

He returns to the subject a little further on:

Still the fact remains, that there has been of late years a fierce and intolerant temper abroad, which scorns and virtually tramples on the little ones of Christ. [13]

He was no longer, and, at the bottom of his heart, he had never been, one of those who speak and act" as if no responsibility attached to wild words and overbearing deeds." [14]

After the "Apologia," I do not think there will be found a single page of his which confirms Hort's severe criticism. His exquisite irony became more tender, and he no longer approaches souls except to gently win their secrets and to yield his own to them. To all he seems to say what Gerontius said to the guardian angel:

I would have nothing but to speak with thee

For speaking's sake. I wish to hold with thee

Conscious communion.

This last phrase ought to serve as a motto for all Christian controversy. Is it not a repetition of the words which Newman had engraved above his cardinal's coat-of-arms -- Cor ad cor

loquitur? I am unable to give long examples of this cordial style of controversy. It must suffice to detach the conclusion of the answer of Newman to Pusey's "Eirenicon." That excellent man, in his invitation to Catholics to discuss proposals for peace, had spoken with an irritating want of tact

about the devotion to the Blessed Virgin. After having discussed each of his allegations, Newman concludes his answer with these gentle and firm words:

And now, after having said so much as this, bear with me, my dear friend, if I end with an expostulation. Have you not been touching us on a very tender point in a very rude way? Is it not the effect of what you have said to expose her to scorn and obloquy, who is dearer to us than any other creature? Have you even hinted that our love for her is anything else than an abuse ? Have you thrown her one kind word yourself all through your book? I trust so, but I have not lighted upon one. And yet I know you love her well. Can you wonder, then can I complain much, much as I grieve that men should utterly misconceive of you, and are blind to the fact that you have put the whole argument between you and us on a new footing? . . . They have not done you justice here; because in truth, the honour of our Lady is dearer to them than the conversion of England. [15]

And there you have the elements of an incomparable swayer of hearts. If I have brought to light some of the characteristic traits of Newman's feeling, there will be less trouble, I do not say to define, but to explain, the extraordinary attraction which he exercised over the majority of those who came near him. he is at once so near and so far from us. So near, as has just been seen. There is nothing heroic in his affection, nothing which surpasses the proportions of everyday humanity. When, with that piercing insight, of which so few men are capable, he makes the inspection of his whole heart, he inspects ours as well, and, like another, handing over his own secret to us, he tells us the secret of the whole world. Lile Fénelon, he is one of those men to whom we can tell everything, because we feel that no revelation will surprise him. Besides, how are we to doubt the infinite forbearance of a Christian, of a priest, who we know despises himself? Does it not seem also that a man who refuses to impose upon us is really always imposing upon us? We are always so quick to conceal our own wretchedness with some cloak that we come to regard him, who makes the simple avowal that he is a man, as no ordinary mortal. We place him against his will on the pedestal from which he persists in descending. If he lets us see him to be such as we are, it is because he is greater than we. On the other hand, it can also be said, without too much refining, that a Newman less distant, less detached, of a more simple and lively affection, would have less hold upon us. Sufficiently affectionate to desire to have our heart, he is not sufficiently so to place himself at our mercy. He yields and shields himself at the same time. He attracts us and avoids us. Is not the same law always observable in the humblest as in the most exalted forms of love? And might it not be said that, for a heart truly to attract us, it is necessary that it should hardly find any difficulty in living without us? A saint absolutely detached from every creature provokes my wonder rather than my love. I admire him, I venerate him, I invoke him. He is already no longer of this world. "When he opens his arms," I "fall at his feet." On the contrary, a heart, which I feel is too like mine, deserves only love. Newman (he sometimes recognized it in himself) has a foot in both worlds. Solitude is grievous to him, and yet I know that he can live alone. The most simple of men, and one with the least affectation of solemnity, he humbles himself, without knowing it, when he comes to me, and this condescension, which he never makes me feel, gives to the slightest tokens of his affection an infinite price. He thirsts for love, and yet the better part of his life is passed in a desert where he meets only with God. Like Fénelon, like Lacordaire (I choose on purpose enchanters who are quite unlike each other), Newman is altogether both my brother and my hero. [16]

And there you have the elements of an incomparable swayer of hearts. If I have brought to light some of the characteristic traits of Newman's feeling, there will be less trouble, I do not say to define, but to explain, the extraordinary attraction which he exercised over the majority of those who came near him. he is at once so near and so far from us. So near, as has just been seen. There is nothing heroic in his affection, nothing which surpasses the proportions of everyday humanity. When, with that piercing insight, of which so few men are capable, he makes the inspection of his whole heart, he inspects ours as well, and, like another, handing over his own secret to us, he tells us the secret of the whole world. Lile Fénelon, he is one of those men to whom we can tell everything, because we feel that no revelation will surprise him. Besides, how are we to doubt the infinite forbearance of a Christian, of a priest, who we know despises himself? Does it not seem also that a man who refuses to impose upon us is really always imposing upon us? We are always so quick to conceal our own wretchedness with some cloak that we come to regard him, who makes the simple avowal that he is a man, as no ordinary mortal. We place him against his will on the pedestal from which he persists in descending. If he lets us see him to be such as we are, it is because he is greater than we. On the other hand, it can also be said, without too much refining, that a Newman less distant, less detached, of a more simple and lively affection, would have less hold upon us. Sufficiently affectionate to desire to have our heart, he is not sufficiently so to place himself at our mercy. He yields and shields himself at the same time. He attracts us and avoids us. Is not the same law always observable in the humblest as in the most exalted forms of love? And might it not be said that, for a heart truly to attract us, it is necessary that it should hardly find any difficulty in living without us? A saint absolutely detached from every creature provokes my wonder rather than my love. I admire him, I venerate him, I invoke him. He is already no longer of this world. "When he opens his arms," I "fall at his feet." On the contrary, a heart, which I feel is too like mine, deserves only love. Newman (he sometimes recognized it in himself) has a foot in both worlds. Solitude is grievous to him, and yet I know that he can live alone. The most simple of men, and one with the least affectation of solemnity, he humbles himself, without knowing it, when he comes to me, and this condescension, which he never makes me feel, gives to the slightest tokens of his affection an infinite price. He thirsts for love, and yet the better part of his life is passed in a desert where he meets only with God. Like Fénelon, like Lacordaire (I choose on purpose enchanters who are quite unlike each other), Newman is altogether both my brother and my hero. [16]

Notes:

1. "Life and Letters of F.J.A. Hort," i. 231 (Macmillan). The value of this admirable man is not sufficiently known among us. Yet there are several who consider -- and it seems to me they are right -- that in the famous trio, Lightfoot, Westcott, Hort, it is the last who must be put in the first rank. These two volumes of letters make one of the best books I know.

2. Hort said, in the same place, "Him I all but worship."

3. Hort, id. ii. 424.

4. "Prophetical Office," lecture iii. 100-101.

5. "Prophetical Office," lecture iii. 121-125.

6. Id. lecture iv. 131.

7. Id. lecture ii. 73-79.

8. Cf. Baudrillart, " Bodin et son Temps," p. 103.

9. "Life and Letters of F. J. A. Hort," i. 105. [There do not seem to be any "sneers at the Prayer-book," as such, in "Loss and Gain." --TRANSLATOR.]

10. "Loss and Gain," pt. iii. chap. ii. 270.

11. Cf. " L'Inquiétude Religieuse.

12. Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, reprinted in "Certain Difficulties felt by Anglicans," ii. 300.

13. "Certain Difficulties," ii. 339

14. Id. ii. 176.

15. "Certain Difficulties," ii. 115, 116.

16. He tried to define this char in speaking of St. Chrysostom. It would not be very difficult to show that the "discriminating affectionateness," which, for him, explains the indescribable attraction of St. Chrysostom, bears a very close resemblance to the description which I have just outlined. Cf. "Historical sketches," ii. 284-289.