Per Humanitatem

Per Humanitatem

By Bronwen McShea - New Haven, Connecticut, USA - Advent/Christmas 2010

The Latin phrase "per humanitatem" is taken from the opening of the Confessions by Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430). There, Augustine uttered his beautiful declaration to God, "Thou hast made us for Thyself and our hearts are restless till they rest in Thee." He also described his Christian faith as something that both yearns for God and comes as a gift from Him through the person of Jesus of Nazareth and through the preaching of His ministers: "My faith cries to Thee, the faith that You have given me, that you have inbreathed in me, through the humanity of Your Son and by the ministry of Your preacher." Per humanitatem filii tui, per ministerium praedicatoris tui: Augustine affirms that his life of faith, "inbreathed" in him by the very Spirit of God, is also a very human affair.

Christianity proposes to the world a most startling idea, that God has become a man, so that all men and women may -- together in mystical communion -- become one with God. This is what Christmas Day, December 25, celebrates. This is why, in the Catholic Church, the birth of the infant Jesus is commemorated with a Mass, "Christ's Mass," in which His Passion and Crucifixion are also commemorated, because in giving Himself to be born as a human being, God gives Himself to die, too, and in dying makes possible the revivication of human souls withering in sin. In this, He makes possible the resurrection of all flesh, blood, bone, dust -- all that is subject to dissipation and decay.

Over the centuries, many have, of course, rejected or moderated these ideas. The God of Christianity, a Jew who speaks Aramaic, who befriends prostitutes, tax men, and soldiers, who sheds blood, hangs on a cross, and seems, through it all, to be unusually close to His mother, has seemed to many to be "too human" to be God. Others have rejected Christianity, quite differently, because its understanding of humanity seems overburdened by notions of divinity and purity, by the guilt and spiritual ambition that Scriptural injunctions like "Be perfect as your father in heaven is perfect" engender. Many others have simply dismissed doctrines like the Incarnation, the Virgin Birth, and the Resurrection as nonsense. Still others have come to believe that men and women -- or at least a select few of them -- can become like God without the indecorous help of a crucified Lord, certainly without the help of His preachers, and very possibly without God's having to exist at all.

Our world today is informed by all these ideas. Christian, semi-Christian, and anti-Christian principles are at work in our institutions, cultures, and our personalities in different ways, sometimes clashing with one another, often co-existing peaceably or indifferently. Understanding how to flourish as a Christian and as a human being in such a world can be confusing and painful, even where Christian faith brings with it "pearls of great price," experiences of real peace and joy which betoken the lasting gifts of Heaven. What in this world should be embraced? What must be rejected? What must be loved from the depths of our hearts yet also sacrificed?

Life in this world is no easier for those who consent to follow in the paths the Catholic Church marks out for her members. The Church offers many guidelines for how to structure our interior and common lives, our relationship to God and to Creation, and our relations with one another. Yet abiding by these guidelines can be extremely discomfiting to Catholics and to others. Certain teachings of the Church, such as prohibitions on divorce and contraception, confound categories of thinking and ethical consideration which seem sufficient and reasonable to most people, including many who profess Christianity. At the same time, those who willingly struggle, sometimes succeeding, sometimes not, to remain faithful to the Church's teachings tend to be changed through the experience and to come to see themselves and the world differently, in ways that defy their earlier expectations about what would be most burdensome to them, or what might be the sources of unimagined happiness.

With a great variety of such experiences in view, PILGRIM is offered as a forum for Catholics, and for all who may be drawn to Catholic ideas and approaches to life, to reflect critically and creatively on the challenges and wonders of life in the world and life within the Church. Here, we are interested especially in dilemmas of conscience and action faced by men and women of Christian faith. We are also interested in the full range of experiences -- joyful, sorrowful, mundane, illuminating, and glorious -- that make us human and form the landscape in which Christians pursue their "adventures in grace," to borrow a phrase from Raïssa Maritain.

At PILGRIM, contributors are invited to reflect freely on what distinguishes the Catholic experience of life from various alternatives. What about Catholicism is so compelling to those, like Augustine, who decide as adults to change their lives and enter the Church by choice? Do "cradle Catholics" see the world and behave differently than others? To what degree should Catholics differ from others?

PILGRIM is offered, as well, as a forum in which Catholic writers and artists may be free simply to discuss, as Catholics, all manner of subjects of concern to them without remaining mired in apologetic or defensive discussions about first principles. Here, Catholics are just as free to allude matter-of-factly to, say, Christ's real presence in the Eucharist or to their communion with the dead as they are free to discuss very secular topics in largely secular terms -- without having to burden their prose with theological or doctrinal justifications either for their Catholic beliefs or for their interest in worldlier matters.

As a humanistic enterprise, PILGRIM is also a forum for Catholics, and those sympathetic to Catholic ideas and approaches to life, to develop their capacities for criticial thought, creativity, and concern for one another and for all God's Creation. I have high hopes about what I would like PILGRIM to become not simply as a journal about faith and human experience, but also as a kind of workshop or birth chamber of Catholic culture-making.

Since it is the nature of culture to mature organically, I should not say too much about PILGRIM's artistic purposes. I would like to be as surprised as anyone about the poems, paintings, stories, and so on which will appear in future issues of the journal! I will say, however, that in general our artistic interests stem from our larger interests in faith and life in the world as it is really lived. Our goal is to portray human life as it is really experienced, while assuming, in faith, that human life has a very definite purpose: to know, serve, and love God as He has made Himself known to us in history. We will convey these portraits, too, in order to offer sympathy as well as food for thought and instruction, based on lived experience, to readers in search of such fruits of human reflection and fellowship. We will honor and reflect upon extraordinary as well as very ordinary human lives, acts of holiness and virtue, and moral and intellectual struggles. If there is something stirring or troubling to the life of Christian faith, witnessed in the nooks and crannies of a very ordinary domestic scene, in a shopping mall or Wal-Mart, in a comic book or TV show, in the back pews of a suburban parish church, or in a seedy bar on the wrong side of town, we wish to consider it lovingly, alongside discoveries made inside stupefying Baroque basilicas, opera halls and art museums, at the top of mountains and skyscrapers, or in great books passed onto us by our wisest teachers.

At PILGRIM, we are determined to resist the spirits of ideological rivalry and acrimony which at times poison discussions about the relationship of religion to society, and which all too often prevent people who worship together in the same Church from communicating meaningfully and openly with one another. I know from my own experience that these spirits can be seductive and are sometimes difficult to resist while one is still maturing in one's faith and discerning the social implications of one's religious commitments. Knowing intimately what rivalry and acrimony tend to look, feel, and sound like, I will be particularly vigilant, as PILGRIM's editor, to cultivate in this journal a spirit of patience, respect, and sincerity toward all men and women.

Our commitment to humane, respectful attitudes is motivated by that Christian faith that cries up to God, as Augustine puts it. We believe that strong Christian faith and genuine openness to the experience of others go hand in hand. Striving to embody a genuinely Catholic spirit, we will often include contributions from writers and artists who do not share fully in the Catholic faith or or profess Christianity at all, because we know that maturing humanity and faith depend crucially upon encounters with unexpected people in unexpected places. For, as an old Gaelic rune puts it, "Often, often, often/Goes the Christ in the stranger's guise."

Our purpose, however, is neither to apologize for the Catholic faith or to facilitate ecumenical or interfaith dialogues: these are important Christian apostolates, but they are not ours. We will neither bracket aside what makes us distinctively Catholic in favor of a neutral, contentless ground of discussion, nor promote any one, particular "Catholic" agenda for ourselves, for the rest of the Church, or for those who are not Catholic. Our purpose, rather, is to reflect on what Catholic faith, lived in real time and places, by real people, looks, feels, and sounds like, how it deals with problems such as sin and death, and what -- and whom -- it sees, serves, and loves.

Our mission is a challenging one that may take a long time to achieve with real power and grace. As the journal's founding editor, I take full responsibility for its tone, its commitments, and for all the ways it may fall short of its goals and standards. I invite readers to offer criticisms and advice, and I avidly encourage them, as well, if they have something to offer, to submit essays and artistic content for possible publication in one of our upcoming issues. I encourage those who have not been published before, and are moved in some way by what they encounter here on our website, to give us a try.

I should add that PILGRIM's name was originally inspired by words from one of the Eucharistic prayers of the Mass: "All Creation rightly gives you praise. All life, all holiness comes from you through your Son.... Strengthen in faith and love your pilgrim Church on earth...." If I could sum up, then, in my own words, what PILGRIM is all about, it is a journal that is intensely interested in the drama of human life as it is both lived and witnessed by God's "pilgrim Church on earth."

Centuries ago, Bishop Augustine understood the human need for writing down, for others, one's personal experiences with sin, repentance, and life both as it is truly lived in the world and renewed by the life of God. In the Confessions, he movingly describes to God why he penned an account of his own life for others to read, rather than confessing only privately to God. Because, he says, the "believing sons of men...those who have gone before, and those who are to come after, and those who walk the way of life with me" are the "companions of my joy and sharers of my mortality, my fellow citizens, my fellow pilgrims."

Augustine's writings are most powerful when they express the truth of the human condition -- that we are somehow simultaneously of this present world and yet not of it. That each and every human person is a pilgrim, called to travel to that definite place where each would find God and at last be able to remain with Him -- truly and forever happy -- but also that each is charged to live in this world as humanly as possible, following in the path of Christ's sacred humanity, through to the final hours of His Passion and death on the Cross. Knowing that nothing and no one in this life will escape that final crucible, the Christian pilgrim nevertheless tends diligently to the responsibilities of the everyday, including caring for God's Creation -- the earth upon which he travels, all living things, and his neighbors and fellow pilgrims. Loving our neighbors as we love ourselves means doing what we can to enable God to cultivate in our hearts ever greater, and purified, desires for all that belongs to Heaven, for all the pain and fear and restlessness this maturing of the heart brings. Truth, beauty, goodness, peace -- if we desire these things, we are promised we will be fulfilled beyond all dreaming if only we persevere in the Christian call to repentance and love.

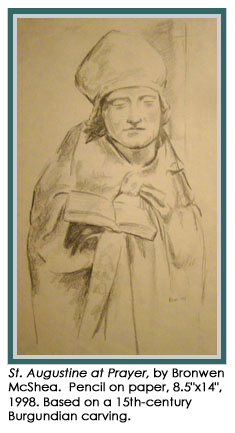

Assuming he doesn't mind, and hoping he's actually quite pleased to oblige, I wish to name Saint Augustine as PILGRIM's patron saint. He's already the patron saint of beer brewers and printers, which signals to me that he has a fondness in his heart for those who seek festive companionship as well as the fellowship that is found in sharing words and images with others.

And so I ask Saint Augustine of Hippo, the Doctor of Grace: Please pray for PILGRIM, for all who make it possible, and for all who come by to visit us on the web. Let us pray with you, as you say in the Confessions: "O Lord have mercy upon me and grant what I desire. For, as I think, my desire is not of the earth, nor of gold or silver and gems or fine raiment or power and glory or lusts of the flesh or the necessities of my body and of this our earthly pilgrimage: all these things shall be added unto us who seek the Kingdom of God and Thy Justice." In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti.

And I wish, to one and to all, many blessings this Advent and Christmas season!