The Pilgrim's Dance

By Lawrence Macala - New Haven, Connecticut, USA - Ordinary Time/All Saints 2011

Let Israel rejoice in its Maker,

let Zion’s sons exult in their king.

Let them praise his name with dancing-- King David

Living each day in the intricacy of our many relationships, casual and intimate, our souls are presented with every kind of experience -- good and bad, welcome and unwelcome -- and we respond to these experiences in different ways. Yet, overarching everything and tempering and shaping all of our experiences, there is to be an extraordinary and transcendent joy. This is the consequence of a simple and singular encompassing truth: throughout all of fallen human history God has been calling a people to himself -- an extraordinary work of the Holy Spirit. It begins with Israel, a people called by God.

Living each day in the intricacy of our many relationships, casual and intimate, our souls are presented with every kind of experience -- good and bad, welcome and unwelcome -- and we respond to these experiences in different ways. Yet, overarching everything and tempering and shaping all of our experiences, there is to be an extraordinary and transcendent joy. This is the consequence of a simple and singular encompassing truth: throughout all of fallen human history God has been calling a people to himself -- an extraordinary work of the Holy Spirit. It begins with Israel, a people called by God.

There is in Charles Williams’ He Came Down from Heaven a succinct, yet pregnant, description of this covenantal work. He writes:

On the arrival at Sinai the salvation of Israel is defined: "Ye shall be unto me a kingdom of priests and an holy nation." It is one of the great dreams -- a people, a nation, a city, a group, any community great or small -- a world of intermediaries, communicating to each other the holy and awful Rites, and yet those Rites (in that state of being) no stranger than common things; the ordinary and the extraordinary made extraordinary and ordinary by joy.

Israel becomes a people, set apart from all other peoples; a nation, possessing the land; a kingdom, with the one who both created and called them being their king, not choosing him as king but being chosen by him. A people, a nation -- but because of who their king is, a religious people, with prescriptive worship: “holy and awful Rites.”

Then the Incarnation! With the coming of the God-Man and the broadening of the call to those who are not of the house of Israel, their intercommunication through the “holy and awful Rites” is dramatically transformed, not in degree, but in its very nature. Williams, in The Forgiveness of Sins, calls this the “new Rite” the “awful and unique Rite.” The former “holy and awful Rites,” the sacrifices offered continually, through the law, by the priests and by the reigning high priest once a year, are now the singular “new Rite,” the “awful and unique Rite” offered by our great High Priest who is a priest forever -- offered once, uniquely, for all time and all eternity. Far more extraordinary but no less ordinary, for, as with the “holy and awful Rites,” the same dual transaction of the ordinary and the extraordinary, by joy, occurs in the celebration of the Eucharist. It was instituted to be memorialized, but it is also a real re-presenting of the new and unique Rite. The institution, on that sacred night before Christ died, was also an extraordinary, indeed unrepeatable, event, which all of Creation had been anticipating and longing to experience. With the coming of the Holy Spirit, that event has now, sacramentally, become ordinary -- in the sense of being common and repeatable.

Then there is the bread. One of the most common substances, throughout history and among peoples, a substance necessary to daily life, has now become extraordinary. The unconsecrated host, a simple piece of bread -- wafer thin, geometrically round, strikingly white -- when consecrated, becomes the body of the eternal Lamb who was slain. And our participation in this event is marked by an unsurpassable joy; the awful joy of communicating with the very “real presence” of Christ within, as our daily, or even less frequent, heavenly bread. Indeed, from the earliest centuries the Church has professed that Christ “for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven” and he himself testified, when he tabernacled among men, that he was the living and life-giving “bread which came down from heaven.” In our partaking of this ordinary bread we are taken up to heaven; heaven comes down to us.

Is not this a participation in the joy that Christ prayed for and that he desired to communicate to the disciples in that same upper room on that very night of institution? Is not this also the fullness of joy that Christ promised to all those who are his? And he also promised that it would be a joy that no one could ever take away. From the truth of these things our mind need never waver, for it is his joy that is in us (John 17), and if it is his joy then its very nature, his nature, is extraordinary -- perfect and eternal. “The ordinary and the extraordinary made extraordinary and ordinary by joy.” The body, blood, soul and divinity of him who created and redeemed the world become our life sustaining food. This is no ordinary banquet!

But his joy in us extends well beyond our Eucharistic encounters with him. T. S. Eliot, in his Four Quartets, presents an image of the majestic and mystical quality of our world which should cause us to see all our daily routines in a different light. Eliot writes:

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.

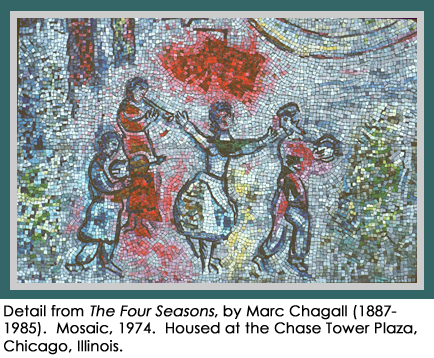

Neither flesh nor fleshless, from nor towards, arrest nor movement, ascent nor decline. At the still point, the center, there is something that transcends all spatial reality. And it transcends all temporal reality as well, for past and future are gathered there. In consequence it cannot be called “fixity.” Christ, the still point of the turning world -- omnipresent: not fixed in space; eternally existing: not fixed in time. To know daily, moment-by-moment, this presence of Christ, the center, with and within, and to be transformed by that abiding presence -- this is our joy. It is the joy of John the Baptist, before he was born, knowing the unborn Christ. It is the joy of the two Marys, in the garden, walking with the resurrected Christ. It is the joy of the Eleven, on Olivet, the mount of ascent, witnessing the departing Christ; a rift in time opening to receive him back into eternity. And it is the joy of the one-hundred and twenty in the upper room, experiencing the Christ, in Tri-Unity, coming to live within. Our prosaic idea of pilgrimage is transformed into the romantic image of the dancer. Why do we dance? It gets us nowhere! We dance for the beauty of it; for the movement, the symmetry of two forms; for the sheer energy and joy. Hardly anyone would say this of walking. Yet of pilgrimage, should we not? All that is true of this image of the dance is true of our daily “walking” with Christ, for without the still point “there would be no dance"; with Christ, “there is only the dance.”

In Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Annie Dillard captures this same sense of daily joy when we are able to see that heaven and earth are truly filled with his glory and then live each moment with a spirit of thankfulness. She ends her reflections this way: “…I go my way, and my left foot says 'Glory,' and my right foot says 'Amen': in and out of Shadow Creek, upstream and down, exultant, in a daze, dancing to the twin silver trumpets of praise.” As we dance the dance of the pilgrim in this life, we are to be an Alleluia from head to toe as each step proclaims either his glory or our Amen to that glory.

Every day and every action throughout all our ordinary days is made extraordinary by the real and continual presence of the Extraordinary One. Ordinary time itself takes on the character of the extraordinary because of the ever present truth of “Christ in you the hope of glory.” This is no ordinary pilgrimage!

So our body, united with Christ in the Eucharist; our soul, united with Christ by his Spirit; body and soul united with Christ in his Body, the holy Catholic Church, is joy. Yet there is a joy that is added to all this, the joy of being co-laborers with Christ, mystically united with him in his extraordinary work of making “all things new.” What appears to be the shadow of his presence with us here will become the real presence of the light of his glory, when all things are brought under his feet. No more sun; no more moon; no more shadows. St. Paul, in writing to the Roman church, says that ”salvation is nearer to us now than when we first believed; the night is far gone, the day is at hand” (Romans 13). We are moving towards our true home and the dance will not end.

This truth is beautifully described by C. S. Lewis in Perelandra where he tells of a world in which the first human pair were tested, as in our world, but remained obedient throughout. Their faithfulness is brought to fruition when they are permitted to enter the place -- the “Holy Mountain” -- where dominion over their world is turned over to them by Perelandra, the angel who had been ruling their world. During this exchange Lewis describes, in transcendent imagery, the plan and purpose of all creation and the nature of all reality -- created, historical, redemptive, eschatological, natural and supernatural. At the beginning of the exchange he says that there passed into them “new modes of joy…as if there were dancing in Deep Heaven.” What he then unfolds is a vision of this “Great Dance.” The angel says it “has begun from before always. There was no time when we did not rejoice before His face as now. The dance which we dance is at the centre and for the dance all things were made.” All creation -- past, present and future -- is part of the Great Dance, as all creation speaks of his glory. And at the center of the dance is Christ: “where Maleldil [Christ] is, there is the center.” Again, “Each thing was made for Him. He is the centre.” All of creation, known and beyond what we know, is moving towards a single consummation, which is the beginning of all that is to come. It is in this consummation that “when he appears then we also will appear with him in glory.” He will “change our lowly body to be like his glorious body,” for “when we see him we shall be made like him, for we shall see him as he is.” This is his promise to those he has called. We will be transformed into the likeness of his glory and a daily joy will then become a joy outside of time. A humanity born in humility is consummated in glory. This is no ordinary end; no ordinary home!

The joy of his presence in the Eucharist and in our daily experiences, and our contemplation of the glory that awaits us at the end of our pilgrimage, ought to bring us back to our ordinary daily world and the truth that the joy of our walking with Christ is for his sake and the sake of his kingdom -- the people he is still calling to himself. In this, Moses, the meekest man in all of Israel, and Christ, the meekest man in all of history, are our teachers. Moses, who was transformed by the thunderous presence of God on that holy mountain -- such that his face glowed with the reflected glory of God -- came down from the mountain. Christ, after being transfigured on another holy mountain -- such that those favored three, in the midst of the radiant revelation of the Tri-Unity, were moved to worship him -- came down. Law and grace each came down to enter back into the daily world of the needy. Each descends from the mount, each to minister to the people: law to those in need of law; and grace, climactically in salvation history, where law was revealed to be inadequate to the people’s need.

What are we to learn from Moses, as our example, but far more from Christ, as our Lord? That we too must be transformed and transfigured by joy. But then we must also realize that he gives us his joy that we might draw others into the dance. The dance is not for us alone! It is for others. We can only learn this by continually deflecting our vision from ourselves to Christ and to others. We may then be privileged to see what C.S. Lewis saw and expressed in a profound and moving way in his address The Weight of Glory. Lewis reflects on our desire for our own good and how we have been deceived by the modern world in two ways regarding this good. On the one hand we have been told that it is selfish to desire our own good; on the other -- more commonly today -- that our own good is to be sought in this world and this world alone. Lewis argues that our greatest good is in God and that this, rightly, ought to be our greatest desire. But desiring our own eternal good is not the end of the matter. He says:

It may be possible for each to think too much of his own potential glory hereafter; it is hardly possible for him to think too often or too deeply about that of his neighbour. The load, or weight, or burden of my neighbour’s glory should be laid daily on my back, a load so heavy that only humility can carry it, and the backs of the proud will be broken. It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilization -- these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit -- immortal horrors or everlasting splendours.

“There are no ordinary people!” The idea runs counter to our common sense and our daily perceptions. The word “mundane” (from the Latin mundus -- world), which referred to earthly things in contrast with heaven, has come to be used to describe the practical, the transient, the ordinary. And if we are honest with ourselves we will admit that this is how we most often perceive our world and others in it. To overcome this shortsightedness we must see anew. Williams, Eliot, and Lewis all saw with vivid clarity what we would do well to learn to see; what Isaiah, the great visionary of Israel, saw and proclaimed over two-thousand years ago: "For behold, I create new heavens and a new earth; and the former things shall not be remembered or come into mind. But be glad and rejoice forever in that which I create; for behold, I create Jerusalem a rejoicing, and her people a joy” (Isaiah 65).

Living each day in the fullness of his joy that others might enter into that very same joy, so that God would delight in creating a people of joy -- this is the vision that we need to keep firmly in our minds each day. God is calling us to himself, to a present joy, to an eternal joy, to a joy that we are to bring to others. Our purpose then, our unending mission in the extraordinary joy of living each day in the real presence of Chris -- accepting all as gift from the Father of lights -- is to draw others, ordinary people, into the dance; not for our sake or to our glory, but for his sake and to his glory; that they, with us, might share in that glory. This becomes the greatest joy of all, since, now, Christ and our neighbor are all and we are servants, instruments of his grace; our daily, earthly lives animated by his eternal, heavenly will. The greatest joy comes in being the servant of all -- the greatest in the kingdom.